Why Do Complex Changes Fail?

Rabbits 🐇🐇🐇 Can Answer All Your Questions On This One

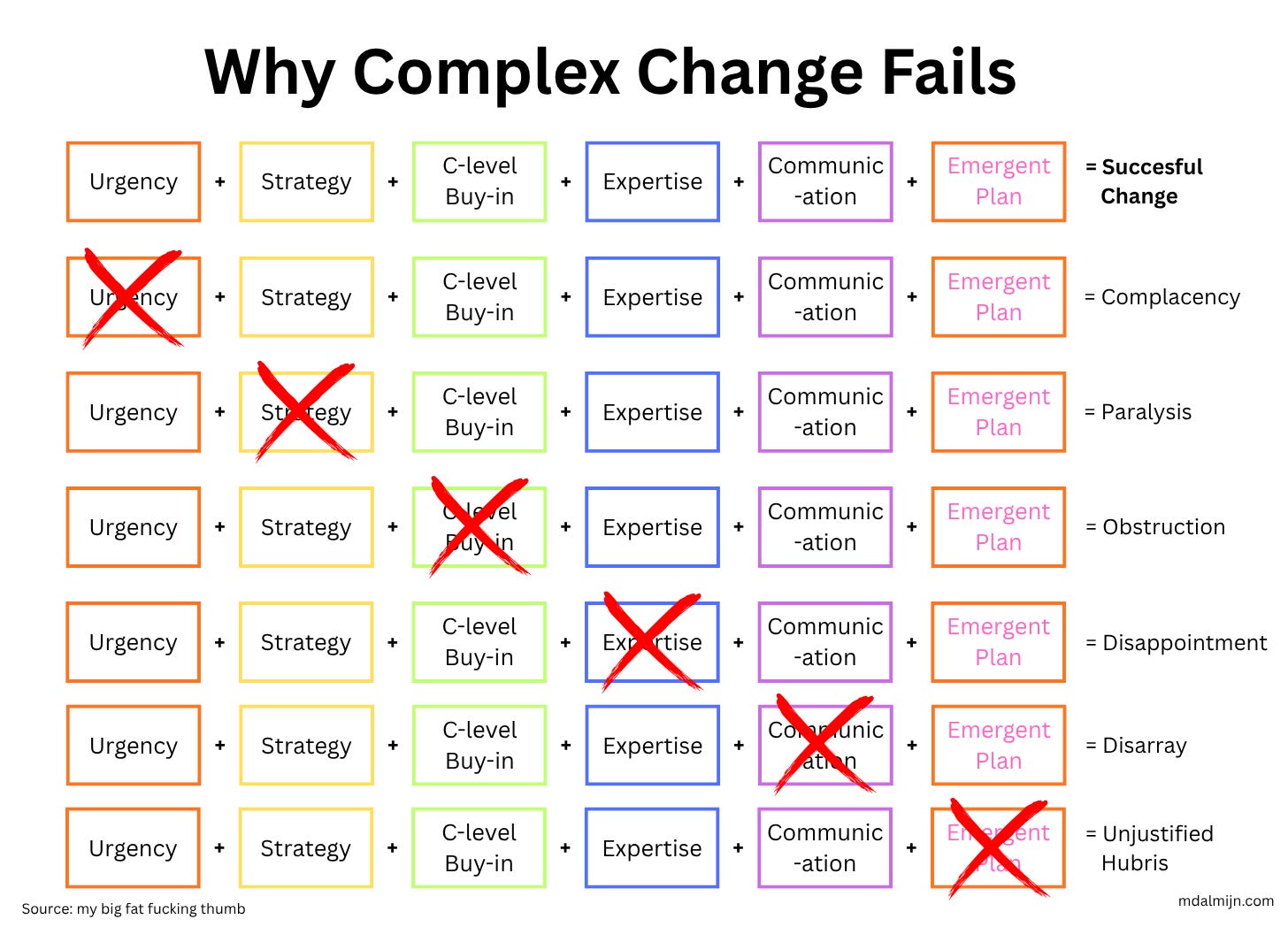

You might have seen this picture with thousands of likes on LinkedIn:

The picture looks extremely clear and makes perfect sense, right?

To implement any successful, complex change, you need Urgency, Strategy, C-level Buy-in, Expertise, Communication, and an Emergent Plan.

If any of these things is missing, you’re bound to fail.

Now look at the picture again. Did you spot the problem?

If you didn’t, pay close attention to the source on the bottom left.

Ha! I fooled you didn’t I?

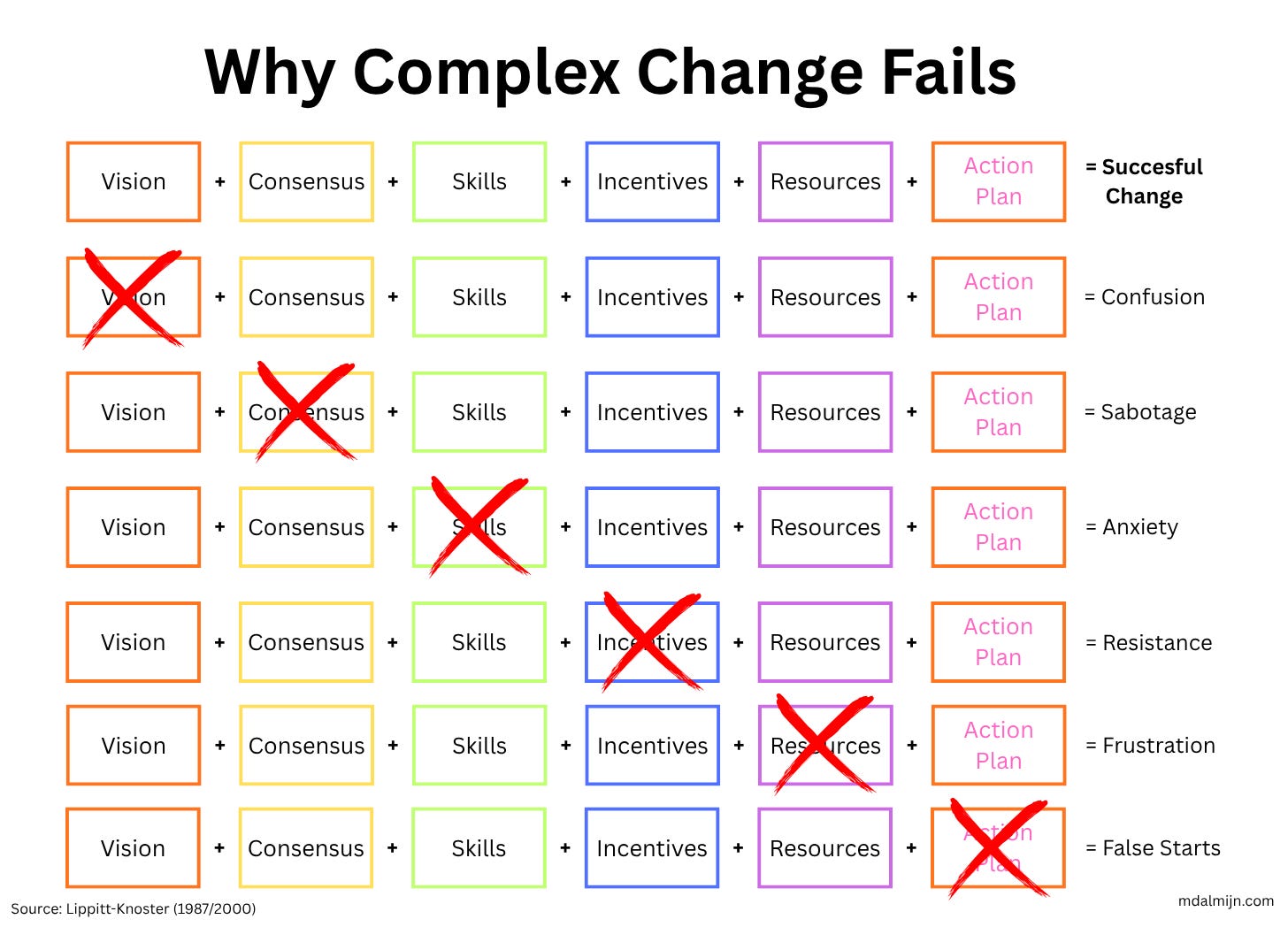

Here’s the real picture you may have seen before, also called the Lippitt-Knoster model.

In the Lippitt-Knoster model, if you don’t have Vision, Consensus, Skills, Incentives, Resources, and an Action Plan, then your complex change will fail.

Based on my experience as a change agent in complex organizations and my understanding of how complex systems work: the model is over-simplistic nonsense.

You might be thinking now: why all the deception and trickery with the self-invented diagram I showed before?

Because both pictures are gross oversimplifications of reality and not why complex changes fail.

All the figures show are twelve different reasons why a complex change can fail.

Anyone can make up six valid reasons why a complex change can fail as I have shown with the first diagram. In fact, all twelve ingredients of both models can be perfectly in place and the complex change can still fail.

Leo Tolstoy expressed it perfectly in his 1877 novel Anna Karenina, also coined as the Anna Karenina Principle:

“All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.”

There are infinite reasons why a complex change can fail. There are far fewer ways it can succeed.

I’ll illustrate this concept by talking about rabbits.

Rabbits in Australia: A Living Experiment On Why Complex Change Fails

Australia has a fluffy demon with pointy ears and a penchant for destruction: the rabbit.

The rabbit is Australia’s most destructive and widespread pest problem. Rabbits were introduced with the arrival of the First Fleet in 1788. Somewhere around the 1920s their population peaked with 10 billion critters.

In Australia, all the ingredients for the Lippitt-Knoster model have been in place for more than 200 years:

Vision: a rabbitless Australia.

Consensus: almost everybody agrees getting rid of the critters is a good idea.

Skills: the very best experts in the world have been involved.

Incentives: money isn’t an issue.

Resources: resources aren’t an issue.

Action plan: a clear action plan that’s regularly updated based on the results.

Here are some of the things they tried in Australia to get rid of the rabbits:

Myxoma Virus was introduced in the 1950s. Killed up to 99% of infected rabbits. The rabbits rapidly evolved genetic resistance.

Rabbit Hemorrhagic Disease Virus was introduced in the 1990s. The virus eradicated up to 98% of the rabbit population.

Warren Destruction. Using bulldozers and tractors to collapse the rabbit warrens.

Rabbit-Proof Fences. They built a fence of 3.256 KM in Australia to keep the rabbits out. This fence could cover the Dutch coastline at least seven times.

If you want to have an idea of how far they were willing to go. Here’s a picture of a rabbit with Myxomatosis:

All of these changes made an impact, but none of them produced the desired result: a rabbitless Australia.

What Can We Learn From The Rabbits 🐇🐇🐇 in Australia

Any predetermined linear chain of events, like the Lippitt-Knoster model, is not the answer for making changes to complex systems because the most important ingredient is missing: the specifics of your situation.

Complex change fails because the best biologists and ecologists in the world can’t even predict what happens when you introduce wolves into Yellowstone Park.

The surprising answer to this question is: more beavers.

If you were to go back in time and introduce the wolves again, it wouldn’t necessarily mean the same thing would happen again, because… It’s a complex system with non-deterministic behavior.

There are still around 200 million rabbits in Australia after spending many millions to try and solve it.

Did they make the situation a lot better? Yes.

Did they solve it? Hell no!

We don’t know what we must do to get rid of all rabbits in Australia, because it’s a complex problem..

Yes, having a Vision, Consensus, Skills, Incentives, Resources and an Action Plan still matters, but it’s not nearly enough.

Not even close.

One of the biggest reasons why complex change fails is because we try to depict it in our minds as a linear chain of events with neat steps to follow for success, like the Lippitt-Knoster model.

Complex change frequently fails because we totally misunderstand and misinterpret what the word ‘Complex’ in Complex Change means.

Yes, you need expertise, frameworks, and models, but it won’t be nearly enough.

We will only know what works, once we’ve did the very thing that worked.

The thing that worked may not work again, elsewhere, or even in the same organization. Even if we could repeat it in precisely the same way.

And this, my friends, is why we can’t have nice things.

There is no neat formula, rulebook, or recipe to follow, despite what some experts will try to make you believe.

But it sure looks magnificent on a slide deck!

Great article and I totally agree - the world is not linear, therefore no solution to a complex problem will be linear either, regardless of what we try and do. I learned that many years ago when trying to install the same solutions in different environments - one always worked, the other took a lot more coaxing. Yeah, so things are like that, and always will be.

If only there would be some framework allowing for inspection and adaptation. On a funny note, we all know the right answer to the rabbit issue - fighting rabbits with rabbits. CRISPR and rabbit killing rabbits (R+). Of course, after a successful RvR+ encounter would play out, R+ would self-destruct in a celebratory manner (lots of product potential there). After inspection, we could adapt the kill count needed for self-destruction. Also, A-B testing..