The Seven Laws of Rules

Rules, Competence and Trust: The Hidden Cost of Rules

Somewhere in Texas in the 90s, warehouse employees noticed the smell of gas.

Management acted adequately and immediately evacuated the building after turning off all potential sources of ignition - lights, power, etc.

After the building was evacuated, two technicians from the local gas company arrived to investigate the matter. Upon arrival, they struggled to navigate in the dark. To their frustration, none of the lights worked.

One of the technicians reached in their pocket to grab a lighter. When he lit the lighter, the warehouse exploded, instantly killing both technicians and sending debris flying up to three miles away.

How could such a tragic mistake happen?

Nominated For the Darwin Awards

The above sequence of events was considered so astoundingly stupid, that in 1999 the technician was posthumously nominated for a Darwin Award. The Darwin Awards recognize individuals who contributed to human evolution by selecting themselves out from the gene pool.

You’re only eligible for the Darwin Awards under three conditions:

Nominee must be dead or rendered sterile.

Astoundingly stupid judgement

Capable of sound judgement

The third condition is key.

One of the first rules anybody learns when investigating a gas leak, is to turn off the lights and power, and to refrain from doing anything that may ignite a spark.

You don’t have to be a gas technician to know this. Almost everybody knows this. The problem is that when mistakes like this one happen, our typical response is to patch these mistakes by adding more rules.

Adding a rule to fix this problem is a massive mistake.

If you add a rule to fix this problem, there is a good chance you will never fix the real problem.

I define a rule is something you must do or follow. If you don’t, there will be (potential) repercussions.

Rules come in many shapes and forms (list not exhaustive):

Plain rules. You’re not allowed to accept more than 50 dollars from anyone in an official capacity or it will be considered a bribe.

Procedural rules. You must exactly follow all the steps in the agreed upon process.

Layers. The moment you have more layers, it (implicitly) comes with rules who is responsible for what, and when you must consult higher-ups.

Hierarchy. You’re not allowed to make certain decisions without approval.

The rules I’m talking about exclude constraints, guidelines or rules imposed by society, e.g. through law. I’m talking about the optional rules that companies intentionally decide to impose on themselves.

The problem with rules is that they might not fix the problem you’re trying to solve. In fact, adding a rule may even make things worse, because you’re only trying to treat the symptoms and not the root cause.

You didn’t fix the original problem and introduced an additional problem: an unnecessary rule you must now follow. Whenever your considering adding a rule to fix a problem, it’s extremely important to consider whether adding a new rule is the right way of solving your problem.

Enter the 7 Laws of Rules, that you can use to determine whether adding a new rule is the right of course of action.

The unfortunate gas leak disaster brings us to the first Law of Rules: rules, even when you’re capable of sound judgement, can’t prevent mistakes.

1. Rules Can’t Prevent Mistakes

No matter what happens, mistakes will be made.

We are fallible and imperfect human beings. Plus we may not even possess the intellect to keep the entirety of all the imposed rules in our head. Especially the more rules there are.

Even if you have rules covering precisely the scenario you’re facing, somebody will still make that mistake despite the rule. The gas leak disaster illustrates this perfectly.

Rules can help decrease the chance of a mistake happening, but they can never eliminate it entirely. Because no matter what you do people will make mistakes in following the rules.

If a mistake happens, carefully reconsider whether adding a new rule is the right course of action. You may be only treating the symptom and not the root cause.

2. Rules Preserve Incompetence

The more competent people are, the less rules they need. Not because those rules don’t matter - they still do - but many rules will be obvious when someone is competent.

Even if you know almost nothing about gas and electricity, it’s immediately obvious you shouldn’t turn on the light. You don’t need a rule for that, except if someone is truly incompetent.

If someone is truly incompetent, the rule won’t fix the actual problem: their incompetence.

Rules often become a special case of what Nassim Taleb calls ‘Minority Rules’. Where the least competent shape the rules that apply for the most competent. The danger of implementing such rules is that they don’t prevent the downside and they may actually cap your upside as well.

Relying on rules to fix incompetence means that rules tend to have a natural tendency to preserve incompetence. Rules that try to address the incompetence treat the symptoms, not the root cause.

When your rules exist to serve the incompetent, then for the competent they will simply serve as a reminder of something they already know, or even get in the way when they are faced with a situation where the rules are meant to be broken.

3. Incompetence and Distrust Fuel More Rules

When you’re in an environment with low trust and lots of incompetent people, then there is one thing you can be sure of: there will be many rules.

Mistakes will be common, due to incompetence, and those mistakes will be immediately turned into rules and processes due to the distrust.

I once worked at a company where the Security Officer said that no integrations were allowed to go live unless he personally reviewed all the code.

They didn’t trust their developers and they were probably right, but implementing such a rule would back-fire and not solve the actual problems.

4. Rules Can Sabotage Competence

Rules cannot increase competence, they can decrease competence. The more rules you have, the more they will undermine competence, because people will begin relying on rules instead of the real-world reason why those rules exist.

A good example of a rule that undermines competence is that every piece of code must be tested by a QA and that they are responsible for quality. By offloading quality to a single department, you will deliver less features, at a slower pace and at a lower quality.

Quality can’t only be the concern of only one subgroup of team members.

5. Rules Generate More Rules

The more reliant we become on rules to make the right decisions, the more elaborate and extensive those rules will become.

When these rules fail, our natural response will be to add more rules or to polish the existing set of rules.

I once saw a Jira workflow with more than 30 statuses. It didn’t start with 30 statuses, but once they went down the path of too many statuses to solve their problems, it became pretty likely that their workflow would explode out of control.

6. Excessive Rules Detach People From Reality

As Dee Hock, the founder and CEO of Visa, expressed much better with the Hock Principle:

“Simple, clear purpose and principles give rise to complex and intelligent behavior. Complex rules and regulations give rise to simple and stupid behavior.” - Dee Hock

Excessive rules are an internal consideration that rarely reflect reality. Reality is too complex to capture in a set of rules to follow, no matter how many rules you come up with.

All you will be doing by having excessive rules is making yourself look dumb. Reality is taxing enough without rules, let alone when you must navigate a maze of rules before you can make a decision.

7. The Spirit of the Rule Is More Important Than the Rule Itself

Rules serve a purpose. When you have rules people must follow, it’s crucial that people understand the intent and purpose behind the rule. Because only if people understand the intent and purpose, do you empower them to break the rule when it’s no longer applies.

If what you’re doing is complex, no rule is perfect, and there will be situations where the rules doesn’t apply. This is what horribly goes wrong when people use Scrum. They try to apply rules that don’t work for their situation.

Usually because they don’t understand the rule, but then they believe they’re doing something wrong instead of the rule being wrong. The 7th rule is more important than any of the rules that precede it, even for the 7 Laws of Rules.

The Unexpected Interplay of Rules, Competence and Trust

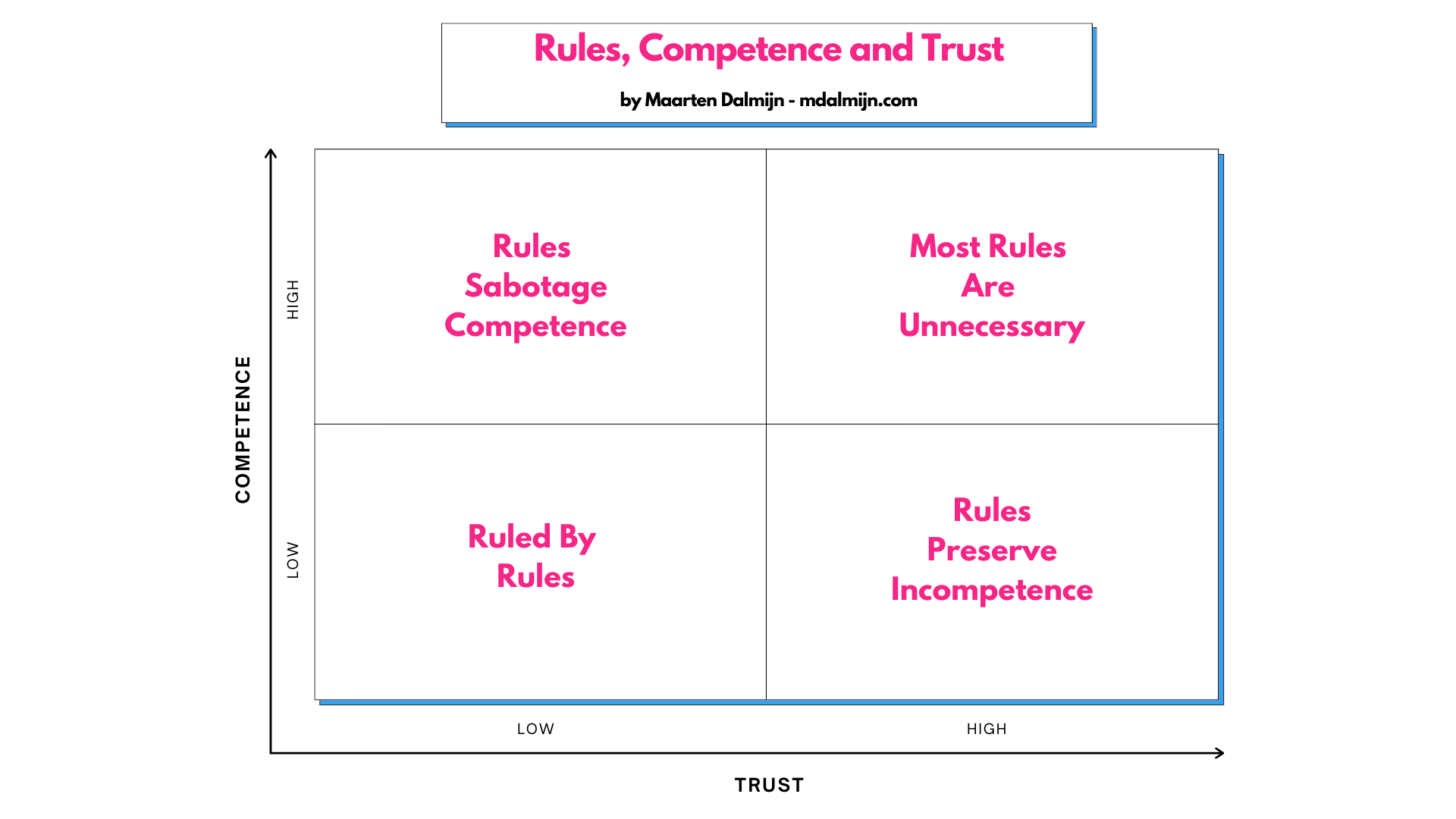

Let’s say you work in an organization with high trust and highly competent people. In such a situation most rules will be unnecessary (top right in the matrix below).

The more rules an organization has, the more busy its people will be with navigating the history of every mistake ever made. They will waste time complying with the internal considerations of an organization as imposed by the rules. This is a daily, sad affair in organizations with low trust and low competence (bottom left in the matrix above).

When you’re ruled by rules, the internal considerations become more important than real-world consequences. The problem with these internal considerations is that they are never more important than the real-world consequences.

Organizations that are ruled by rules, are the kind of organizations where terrible and inhumane disasters can happen because someone blindly follows rules that produce a terrible outcome.

If you’re in a situation with high trust and low competence (top left in the matrix above), then there will be a tendency for rules to preserve your incompetence. Rules frequently provide the illusion that you’re solving your problems. When faced with incompetence rules are often risky, because all they will do is cement your existing incompetence by treating the symptoms and not the problem.

If you’re in a situation where your people are highly competent but low in trust, then the more rules you have, the more you’ll be busy sabotaging your most competent people.

The mistake of not having a rule is not what you should be worried about.

The biggest mistake you can make is having too many rules. When you undermine your most competent people, they will leave to another place where they can actually be competent.

If you have incompetent people whose performance you try to elevate through rules and processes, then you will be dragging your most competent people down.

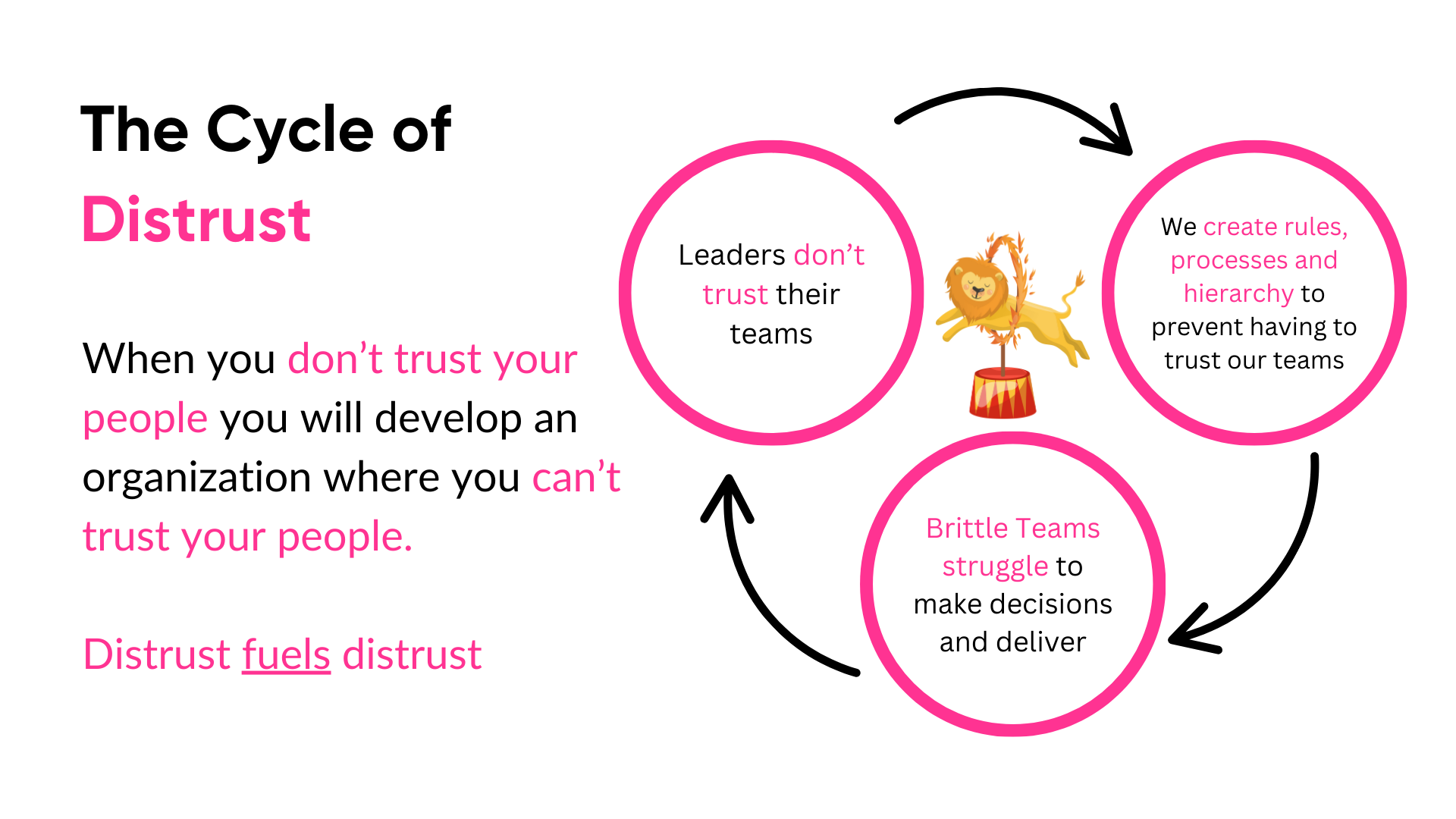

You will be stuck infinitely looping through the Cycle of Distrust, where rules beget more rules, until nobody is capable of doing anything anymore.

Rules cannot prevent incompetent people from making mistakes, they can prevent competent people from doing the right thing.

That’s the real thing you should be worrying about, as competent people intentionally not doing the right thing because they are blinded by rules is what can cause a Prime Minster to Resign.

The Dutch childcare benefits scandal crippled tens of thousands of Dutch families. The Dutch Tax Service wrongly accused 26.000 parents of fraud, leading to tens of thousands of families being driven in severe debt, resulting in suicides, divorces, bankruptcies, foreclosures and kids unnecessarily being placed in foster homes.

The whole affair was considered a systemic failure and caused the Dutch cabinet, including the Prime Minster, to resign. Everybody looked for someone to blame, but there wasn’t a single person to blame, as much as we wanted to find that person.

The more competent your people, the less rules you need. The more rules you have, the less competent your people will become. People are always more important than rules.

In the words of Jesse Frederik, a journalist who wrote a great book about the Dutch Childcare benefits scandal:

“It’s the people, far more than the rules, who ensure our country doesn’t come to a grinding, squeaky halt. People who don’t hide behind regulations because they make life easier, but who try to bend the rules until they are straight again.” - Jesse Frederik, Zo Hadden We Het Niet Bedoeld (This Isn’t What We Intended)

You try to hide behind rules that prevent you from doing the right thing but when your rules are inadequate at some point they will be exposed by reality.

That’s why the 7th rule is the most important: the Spirit of the Rule is always more important than the rule itself. We need more people who are unafraid to bend the rules until they are straight again.

The problem is that these reasonable rule-benders who are seen as unreasonable are precisely the kind of people who are unable survive in the harsh environments imposed by excessive rules.

I was asked to give a talk about software process to a class of Master's Degree students at a university in NJ back in the early 90s. They were mostly contractors to the Army which had an ordinance center not far away. At one point someone asked me, "If we have a sufficiently rigorous process [i.e., one with tight rules and controls] how cheaply do yo think we can hire programmers?" Never before or since have I been asked that. Not a Darwin situation, but I think relevant to your "rules" topic.

It's almost like you worked in government bureaucracies... 😜