The 5 Obstacles to High-Performing Product Teams

The Infuriating Difficulty of Product Management (And What to Do About It)

Why is Product Management so infuriatingly difficult?

By infuriatingly difficult I don’t mean the impostor syndrome you might have suffered from when starting out as a PM. I’m talking about the Herculean task of being a Product Manager at most companies.

Let’s pause and reflect to examine the steps that make us end up in an all-consuming Product Management position.

It all begins with hiring. Before you’re hired as a Product Manager, you must be hired. To get hired you usually have to pass at least three interview rounds, psychological and/or intelligence tests, and possibly even one or more assignments.

Every company has their own obstacle course they’ve carefully crafted to weed out ‘bad’ applicants and let the ‘good’ ones through. This Product Management obstacle course where our misery begins.

With some artistic liberty, we may summarize the Product Management interview process as follows:

“What’s the last bear you’ve wrestled with?”

“How many years of experience do you have wrestling bears?”

“How many different bears can you wrestle at the same time?”

“Can you walk me through all the steps of your bear wrestling approach?”

Most of the interview process revolves around your Product Management experience and expertise a.k.a. how good you’re at wrestling bears.

By the end of the interview process, you feel like the king of wrestling bears. They can throw any bear they might have at you, and you feel confident you’ll rise to the occasion and be able to wrestle it successfully.

Boom! You’ve landed an offer, and you look forward to wrestling all those bears. Then, after starting the job, you immediately witness the following:

Godzilla and King Kong are busy fighting each other and thrashing the whole place to bits. You become frustrated and begin thinking: “WTF, I didn’t sign up for this. I was hired to wrestle bears, so where are all those goddamn bears I can wrestle?”

The Godzilla and King Kong comparison may seem like an exaggeration, but this is usually the surprise that awaits for Product Managers after they’re hired. The job you were hired for is usually not the job you’re going to do. I call this the delta between the theory and the reality of the job. But you only discover the size of the delta after starting the job.

So the big question becomes: why is there such a big delta between the job you’re hired for, and the job you actually must do to get shit done at a company?

Product Management Expertise Isn’t the Problem

I know many people that are looking for Product Management jobs. They often send me some of their assignments and case studies. Examining the awesome work they did, etched the following conviction in my mind:

“If companies are half as good at Product Management as the applicants who complete their assignments and case studies, we would be seeing far better products.”

Most companies do a pretty good job of assessing your experience with wrestling bears. But the fact of the matter is, all that wrestling bear experience is worth nada, because most companies have locked away those bears you can wrestle somewhere in a galaxy far, far away.

The primary reason for this, that within most organization there lurks a big monster: the Kraken.

The Kraken is mythical monster that swallows ships whole and you may have seen it if you’ve ever watched Pirates of the Caribbean. The Kraken is why most organizations suck at Product Management.

All the rules, policies, mindset, culture, processes and bureaucracy give birth to a massive monster with a gazillion tentacles that sabotages Product Teams and their ability to do work to produce the results we want.

The organization, the department, and other business areas, are constantly throwing up internal obstacles that teams must deal with. Outside the team is where most of the power resides, and the teams, which is where most of the work happens, are treated as an after-thought.

It’s not the experience and expertise of their Product Managers, or teams that matters but it is the fact they have a counter-productive organizational system that disempowers teams and prevents them from making the right decision at the right moment.

The organizational system in a company has organically evolved over the years, based on the mindset and problems that were encountered in the past. It’s not necessarily a good fit for the future.

The bigger the kraken, the more your teams will be busy dealing with internal obstacles. A non-exhaustive list of internal obstacles and B.S. teams must deal with that’s indicative of having a gargantuan Kraken:

Scaled Agile Framework (SAFe).

Release Trains

Big Room Planning

PI Planning.

Lots of meetings in general and little time to deep work

Feature-based, team level roadmaps together with timelines

Having too many OKRs.

Massive paper victory business cases to get work prioritized

Elaborate Excel planning sheets that take into account FTE’s

This list doesn’t even really matter, because what it boils down to is this: if even simple things become difficult, then it’s highly likely you’re dealing with one of the tenacles of the Kraken.

When teams are mostly busy dealing with internal obstacles, they become Brittle. Brittle Teams are disconnected from the work to produce the results we want.

What we want is Elastic Teams. These teams don’t waste time fighting the tentacles of the Kraken, and are mostly busy with the very real external obstacles that are discovered as they do the work to produce the results we want. Elastic Teams are flexible and adaptable towards the work to produce the results we want, because they don’t waste time being flexible towards any crazy bureaucratic demands of the company that slow them down.

You might be thinking now: our organization is small, we don’t have a Kraken yet.

I want to stress, most organizations are a few wrong decisions removed from having a Kraken. Even small companies can quickly develop a Kraken with soul-crushing tentacles that produce Brittle Teams: low-performing and disempowered teams.

Let me illustrate this by telling a story from personal experience.

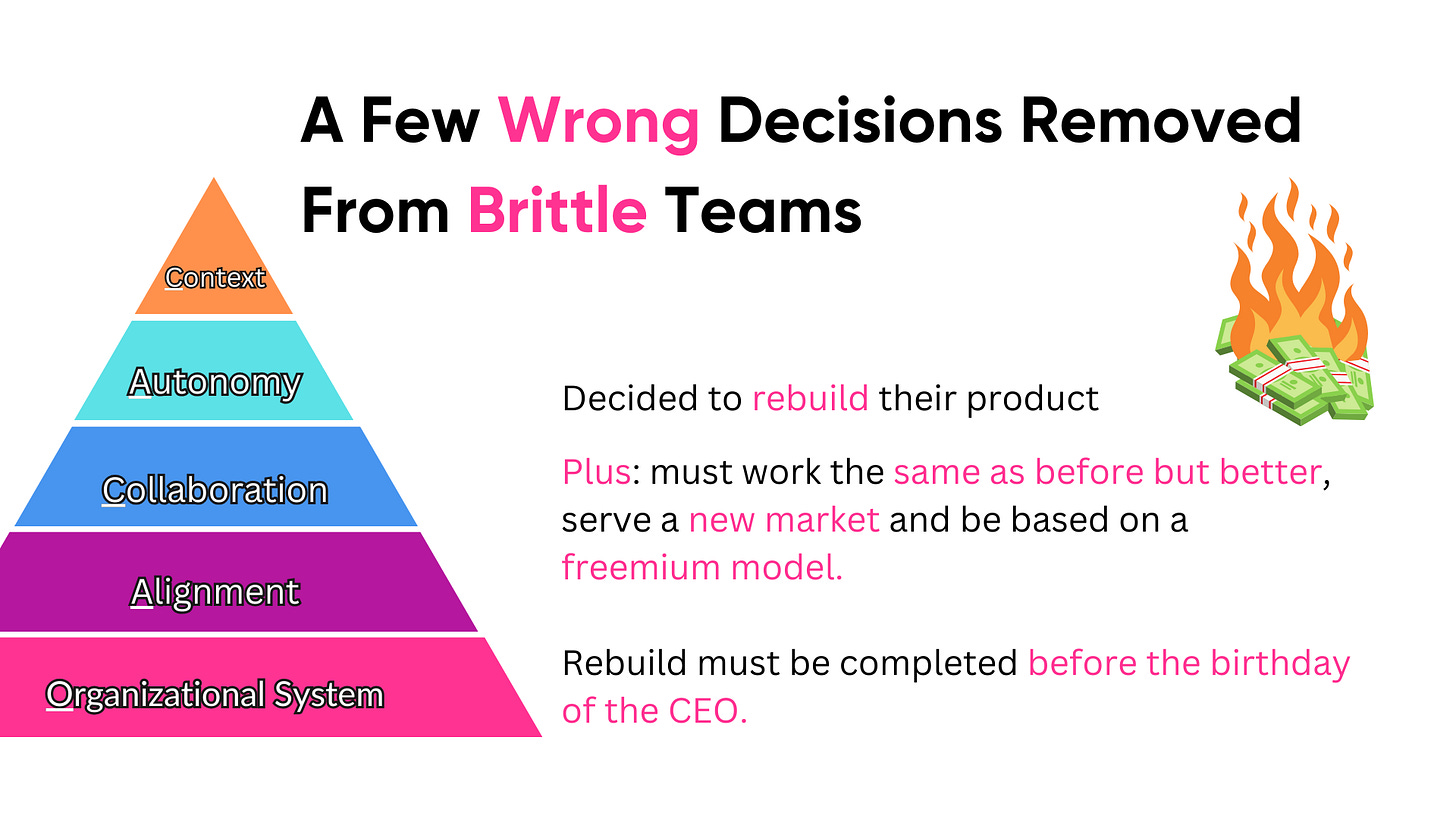

A Few Wrong Decisions Removed From the Soul-Crushing Tentacles of the Kraken

I once worked at an organization with Elastic Teams: high-performing and empowered Product Teams that made the right decision in the right moment. It was awesome to work there, until:

The organization decided to rebuild their whole product. One could argue this was the first mistake, but that’s not where their problems started.

The company decided how the new product should work: “The product should work the same as before but better.”

The deadline for the rebuild was decided by leaders: “Let’s aim to finish the rebuild on the CEO’s birthday to put sufficient pressure on developers to deliver.”

The new product “The rebuild should serve a new market using a product-led freemium model”, while the existing product served a different market using a sales-led model.

The development teams in the company were only happy with point 1. They all agreed the rebuild was necessary. They didn’t have much say on 2, 3 and 4, as all those decisions were made in higher echelons of the organization. These decisions gave rise to a counter-productive organizational system A.K.A. the Kraken.

And that’s where it all went down-hill. The rebuild took much longer than expected, and the end result was a nightmare Frankenstein product that none of our customers really liked.

The rebuilt product was a total dud. The company poured millions of dollars down the drain by a few wrong decision at higher levels in the organization.

We can illustrate the impact of the Kraken on the team level by talking about the 5 Obstacles of High-Performing Teams (CACAO):

Context

Autonomy

Collaboration

Alignment

Organizational System

Impact of the Organizational System

Remember how we talked about any progress not at the bottleneck being an illusion? In most companies, that bottleneck is the organizational system. The organizational system does not support empowered teams, but actively works to disempower them.

The decisions that were made by the leadership team regarding the product rebuild, constrained the Context, Autonomy, Collaboration and Alignment of their teams.

The Organizational System is the bottom of the pyramid, and the base of the pyramid constrains the degrees of freedom at the top: it’s the usually the bottleneck for having Elastic Teams that are empowered and high-performing.

Let’s explore the impact on all the different factors together by beginning to talk about Alignment.

Impact on Alignment

In an ideal world teams are aligned and moving along a shared trajectory. There’s very little cannibalization or competing interests at play.

Let the following sentences sink in once again:

“The Product should work the same as before, but better.”

“The rebuild should serve a new market using a product-led freemium model.”

“Let’s aim to finish the rebuild on the CEO’s birthday to put sufficient pressure on developers to deliver.”

If this is what your leaders are telling you as teams, do you think anyone is going to be aligned? Do you think all the different teams are going to be moving along a shared trajectory together? Hell no!

These are all conflicting directives, that compete and cannibalize each other to set your teams up for failure. The teams were unable to answer any of the following questions:

Is it more important to serve the new market, or to have the product work the same as before? What do we do if it doesn’t work the same as before, but it allows us to better serve the new market?

If better means that it will take longer and we won’t finish the rebuild on time, will we go for better, or we will go for delivering on time?

Is it more important to finish the rebuild on time, or to make sure that we’re moving slowly to allow for adequate discovery to ensure we’re adequately serving the new market?

In short, all of the teams had no clue what we’re trying to achieve with the rebuild. Nobody was aligned on nearly anything. We were constantly arguing and discussing about the right decision to make. We rarely reached consensus. Every argument and discussion was clouded and nearly made impossible by these confusing and competing directives.

Impact on Collaboration

When teams collaborate well, the sum of the parts becomes bigger than the whole. Instead of chasing local optima on the team level, teams explore what the best global optimum might be in conjunction. The end result is that they are making better decisions together and leveraging each other’s experience and expertise.

Lack of alignment severely constrained our collaboration. If we needed help from another team, it almost immediately ended up in a fierce argument, because anything we asked for would almost get stuck in the quicksand of competing interests.

Any ask would mean adjusting and usually increasing the scope, which would put the “Let’s finish it before the birthday of the CEO”-directive at risk.

Asks frequently conflicted with “It should work as the same but before” and if it didn’t work the same as before, was it really better? And better for whom? The existing users of our product, or the new market we were trying to serve?

Collaboration is extremely hard if we don’t know what we’re collaborating on together to achieve.

Impact on Autonomy

If you want teams to have short feedback loops between the work and the results we want, ideally they should be able to make swiftly make decisions without depending on, or waiting for others. You should not have to ask for instructions, but be able to call the shots in the moment.

Because the directives we received were unclear and competing with each other, the teams were put in coordination mode. They were constantly interacting with other teams for clarification and to make sure we were all on the same page. The end result was that the team lacked Autonomy.

Impact on Context

Teams that don’t have context, don’t know the results we want, or why these results matter. Because of this, they can’t incorporate new information to make decisions as they do the work. They’re constantly asking for instructions.

Teams without context don’t have a mission and are not provided with intent. They are disempowered and constantly asking others: tell me what to do. And because leaders didn’t have the full picture together with the relevant context that the teams had, this resulted in many suboptimal decisions being made.

In short, the Kraken, a.k.a. the counter-productive the organizational system that causes the delta between the theory and the practice of Product Management can be defeated by leveraging CACAO to shine a light on where our organizational system is working to disempower our teams and make them brittle.

Great Product Management Means Escaping the Soul-Crushing Tentacles of the Kraken

We’ve all been raised by Product Management books to believe that one day we’ll be that rockstar that commands the product, and helps call the shots. But in all likelihood we won’t. And we’re slowly learning that fact, and we’re very, very pissed off. (You can probably tell I’ve watched Fight Club again recently.)

In most organizations, we’re faced by Kraken with a gazillion tentacles that distracts us and pulls our teams away from the work. We can forget about teams producing the results we want to have. The Kraken with all its soul-crushing tentacles is what makes Product Management infuriatingly difficult in most organization.

Luckily, the Kraken is allergic for chocolate, and we may use it get rid of it’s tentacles.

Instead of worrying so much about hiring Product Managers with the right experience and expertise, we should be worrying far more about the conditions our organization has created for our teams so we can actually leverage the experience and expertise of our Product Managers.

Unless we use CACAO to remove the bottlenecks in our organization for having Elastic Teams - high-performing and empowered Product Teams, organizations will have to settle for Brittle Teams that are disempowered and don’t have a fighting chance to produce the results we want.

The use of memes in this post is exquisite

I'm opting for the dark cacao powder. 1) Still killing the kraken and 2) max flavanols.