Lazy Requirements: Why Worse Is Better

Product Managers: Please Stop Sabotaging Your Requirements and Don't Go Over the Hill.

The most counter-intuitive thing about requirements is that worse is actually better.

Let that sink in.

As Product Managers we usually aim for exactly the opposite. We endlessly rewrite and polish our requirements, trying to chase perfection.

Every draft, tweak and fine-tune brings us closer to feeling proud. We carefully weigh and scrutinize every word before presenting our pristine requirements to the team.

When we finally lay out all the requirements to the team, everybody is quiet. We get zero questions and we pat ourselves on the shoulders for a job well done.

They ask zero questions, because everything is perfectly clear, right?

WRONG!

This kind of diligence is the biggest mistake you can make when formulating requirements. All this effort usually ends up in disaster by making our requirements worse in ways that are nearly impossible to detect and fix.

Why does trying to make our requirements better usually end up making them worse?

Why are gold-plated requirements worse than shoddy requirements?

How can we prevent the effort spent on formulating good requirements from backfiring?

Let’s dig in together!

The Relationship Between Effort And Requirements Quality

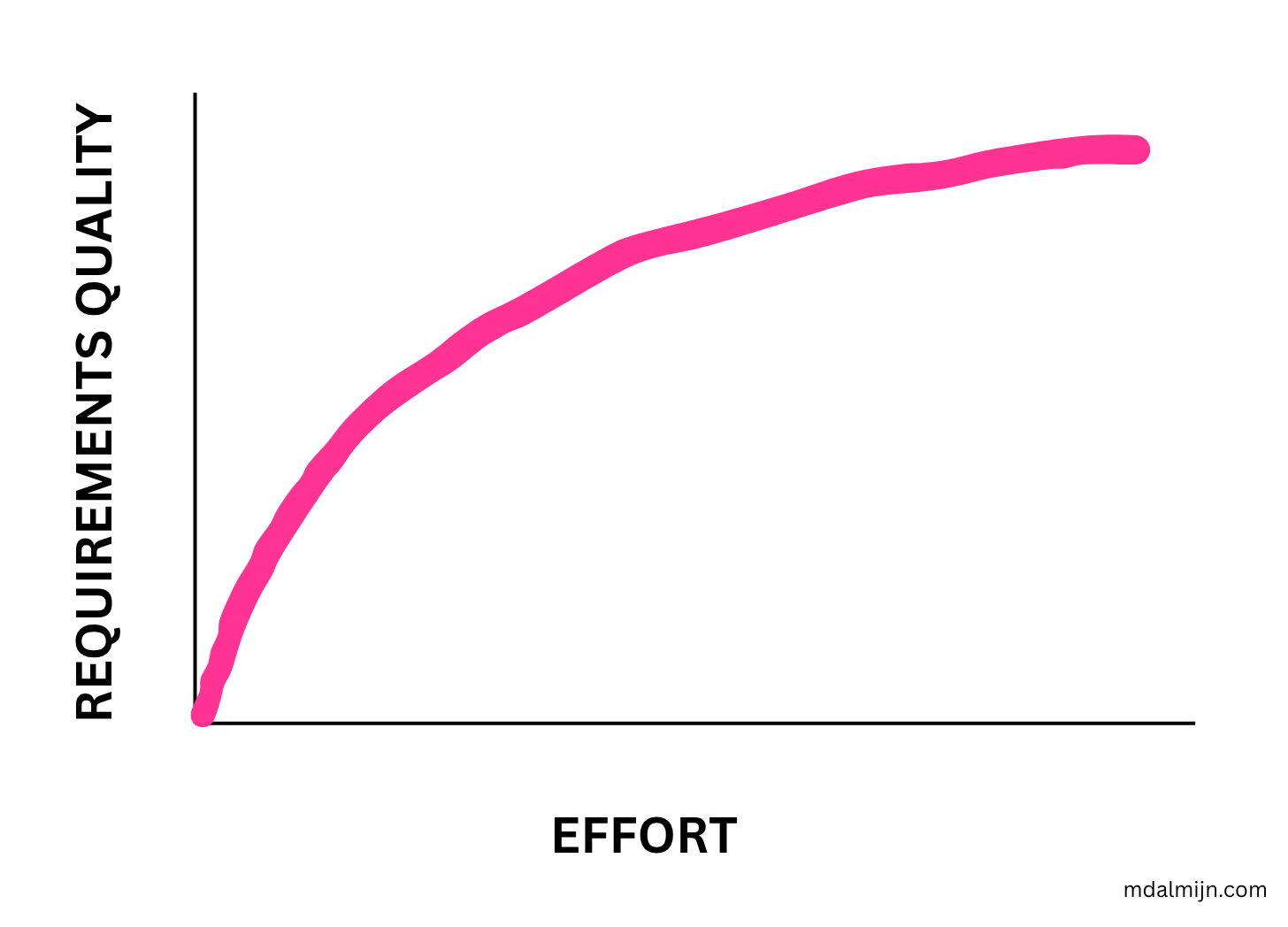

As a Product Manager who was starting out, I used to believe the following relationship between requirements quality and effort existed:

Formulating requirements basically means walking up a hill that becomes less steep as we ascend. As we climb the hill, we reach a point of diminishing returns, where spending more effort doesn’t translate to significantly better requirement quality.

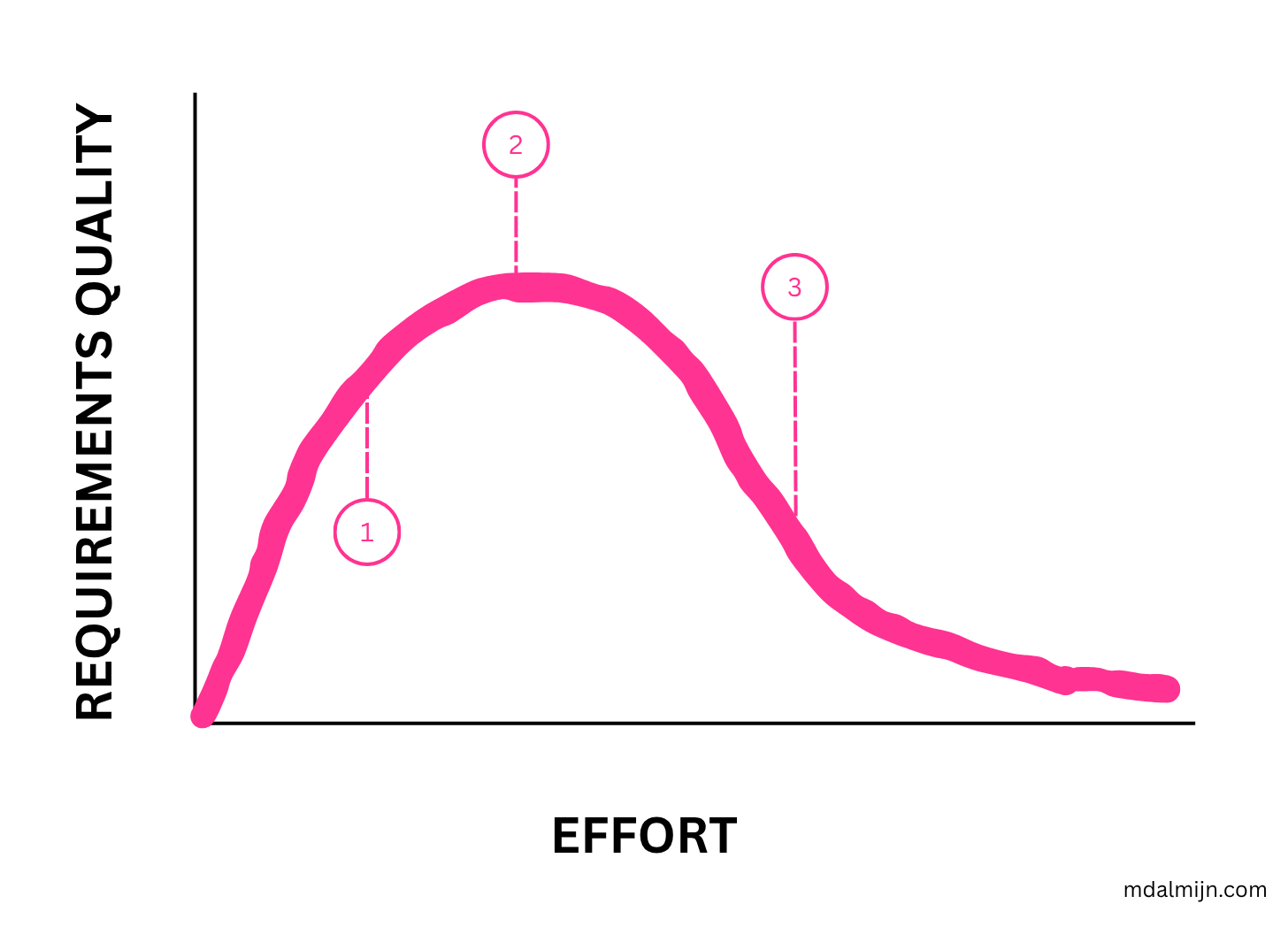

If you believe this mental model of the relationship between effort and requirements quality, then what is the optimal amount of time we should be spending on our requirements before presenting them to the team as a Product Manager?

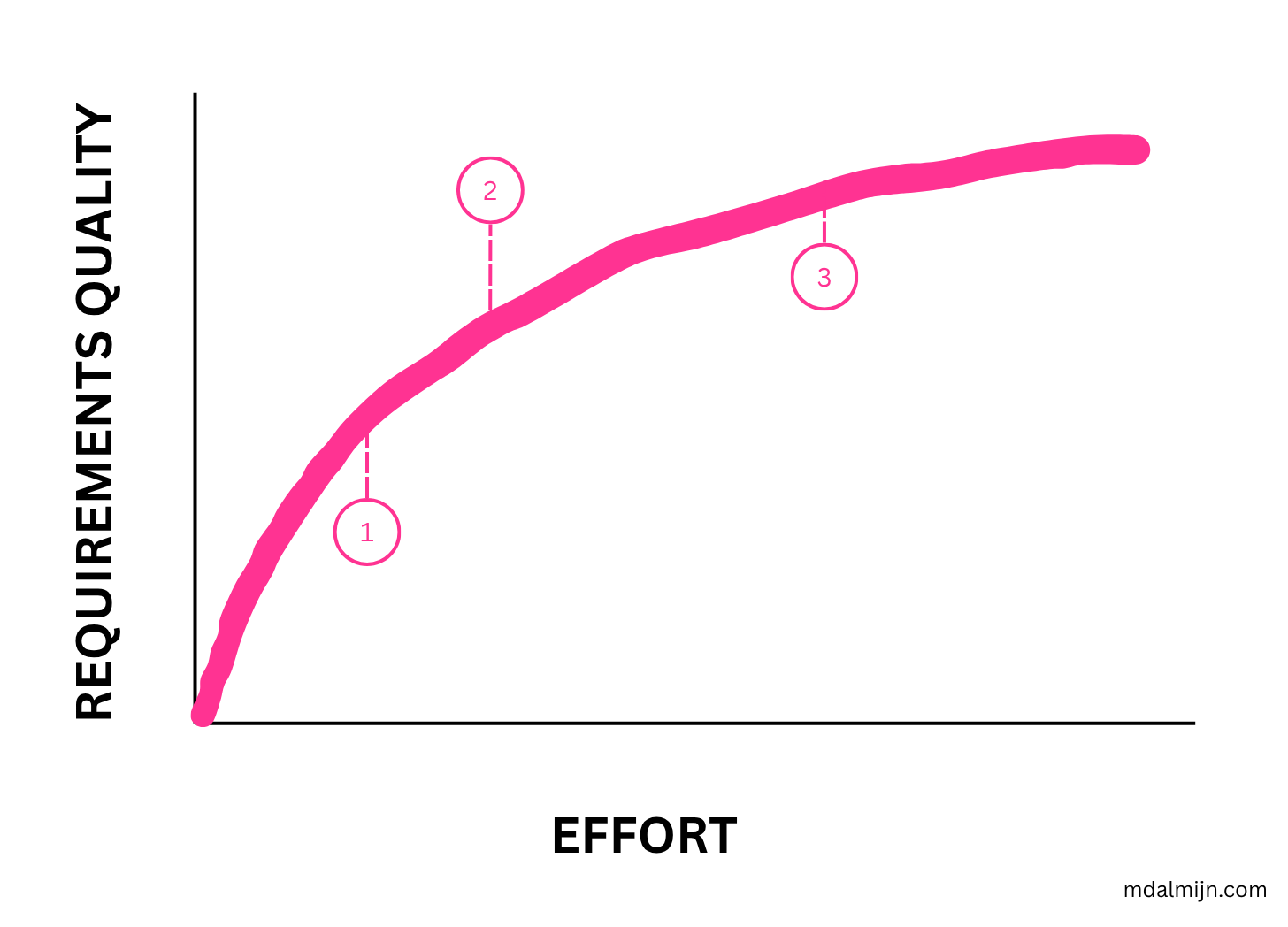

If you believe this mental model, you usually try to end up somewhere around 2, because spending more time beyond the point of diminishing returns doesn’t translate to significantly better results.

The problem is that you don’t know exactly where you are on the curve, so sometimes you end up at point 2, and sometimes you’re closer to point 3. But you definitely don’t want to be around point 1 or lower where you end up with shoddy requirements.

The logical conclusion of the curve is that better is better. Discipline and diligence pay off. More effort spent on requirements actually translates to a better quality of requirements. We’re busy walking up a hill and the closer we get to the peak which we will never reach, the better our requirements will be.

However, I don’t believe this mental model anymore. There is no far-away requirements peak we’re trying to climb. The curve is far too simplistic and doesn’t accurately convey the relationship between requirements quality and the effort we spend on them.

Climbing the Hill of Requirements Quality

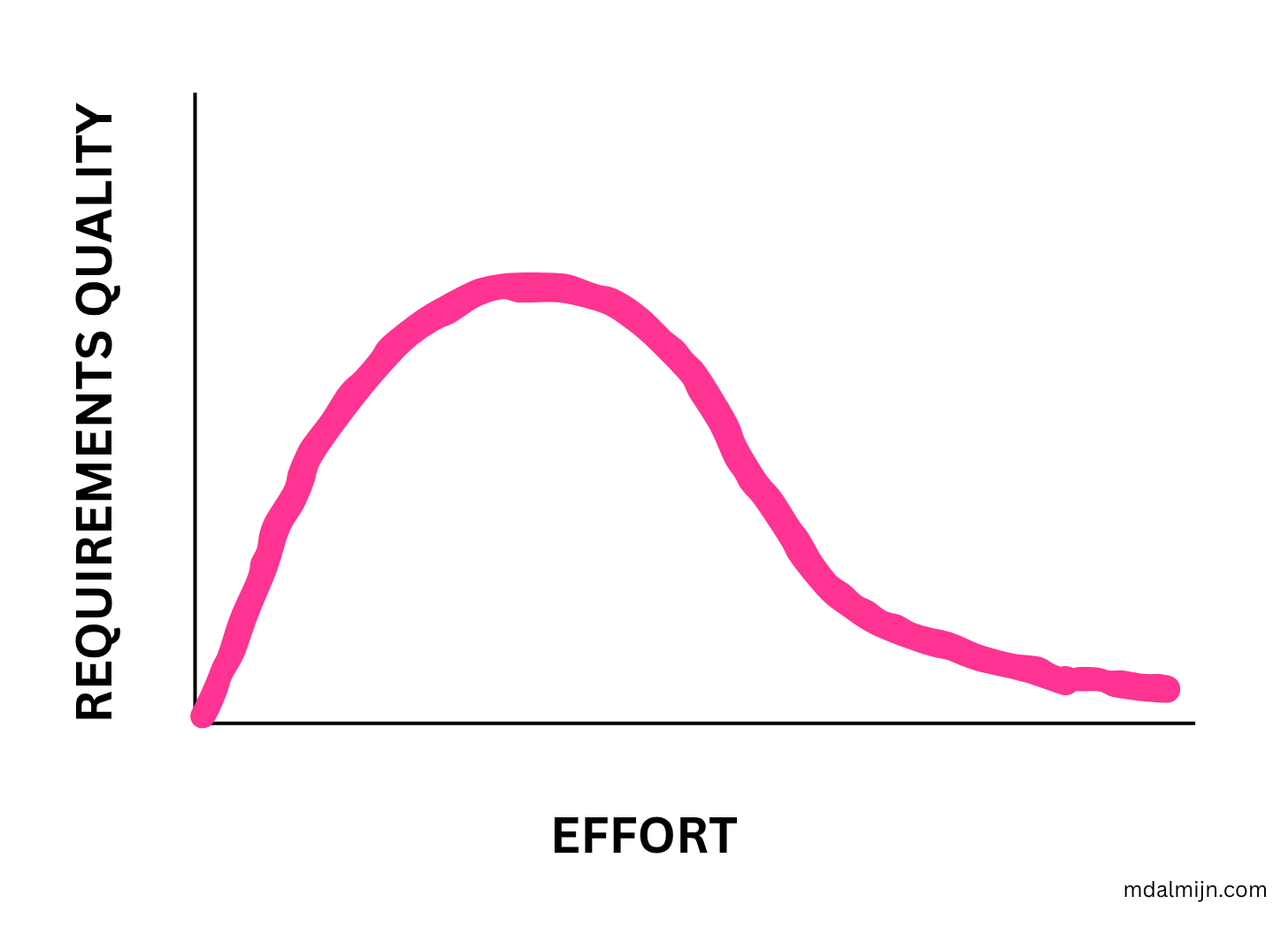

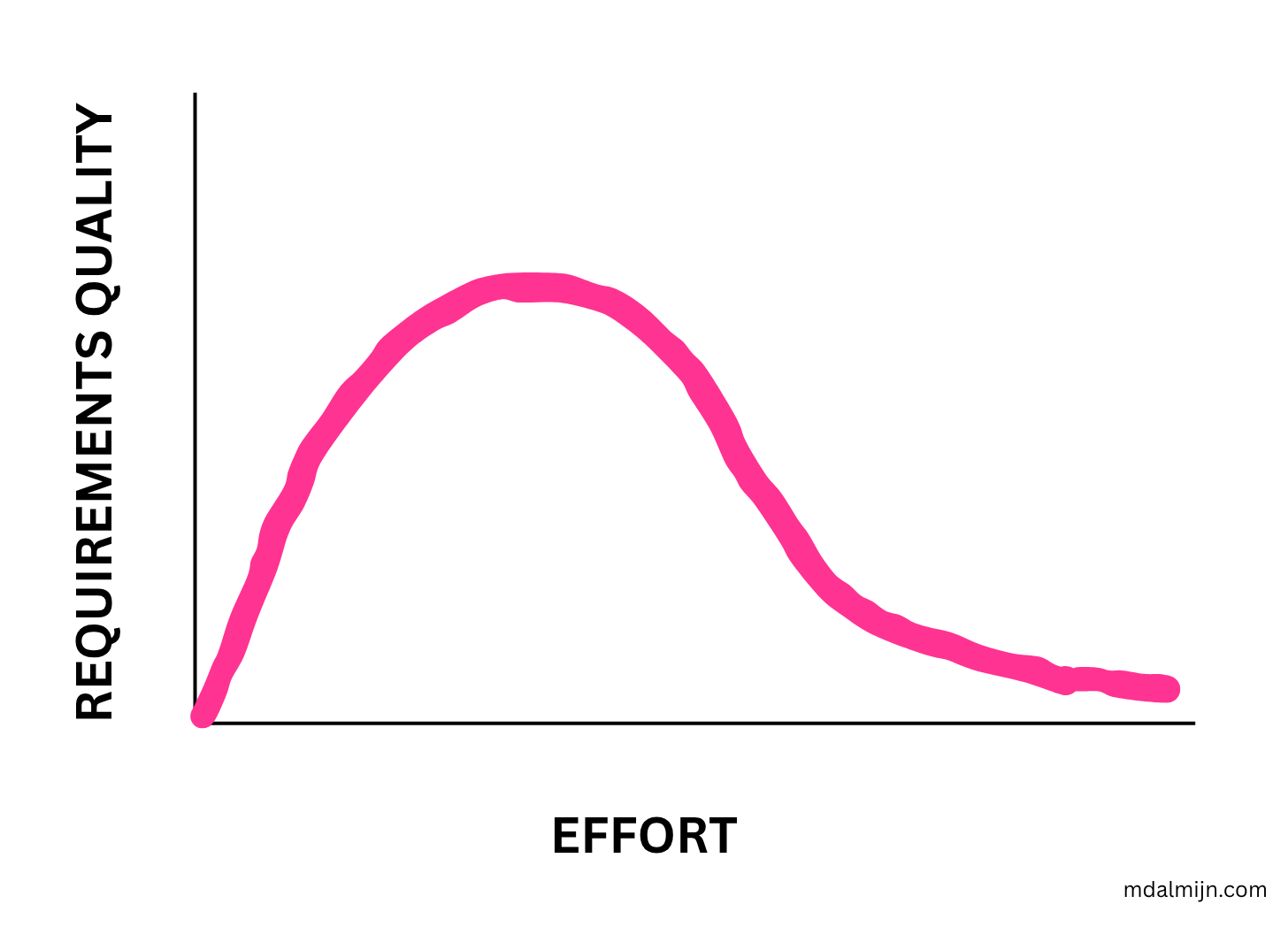

Today I believe the relationship between effort and requirements quality resembles the following curve:

As you spend more effort on the requirements before presenting them to the team, the quality of your requirements becomes better until you go over the hill and the requirements become worse.

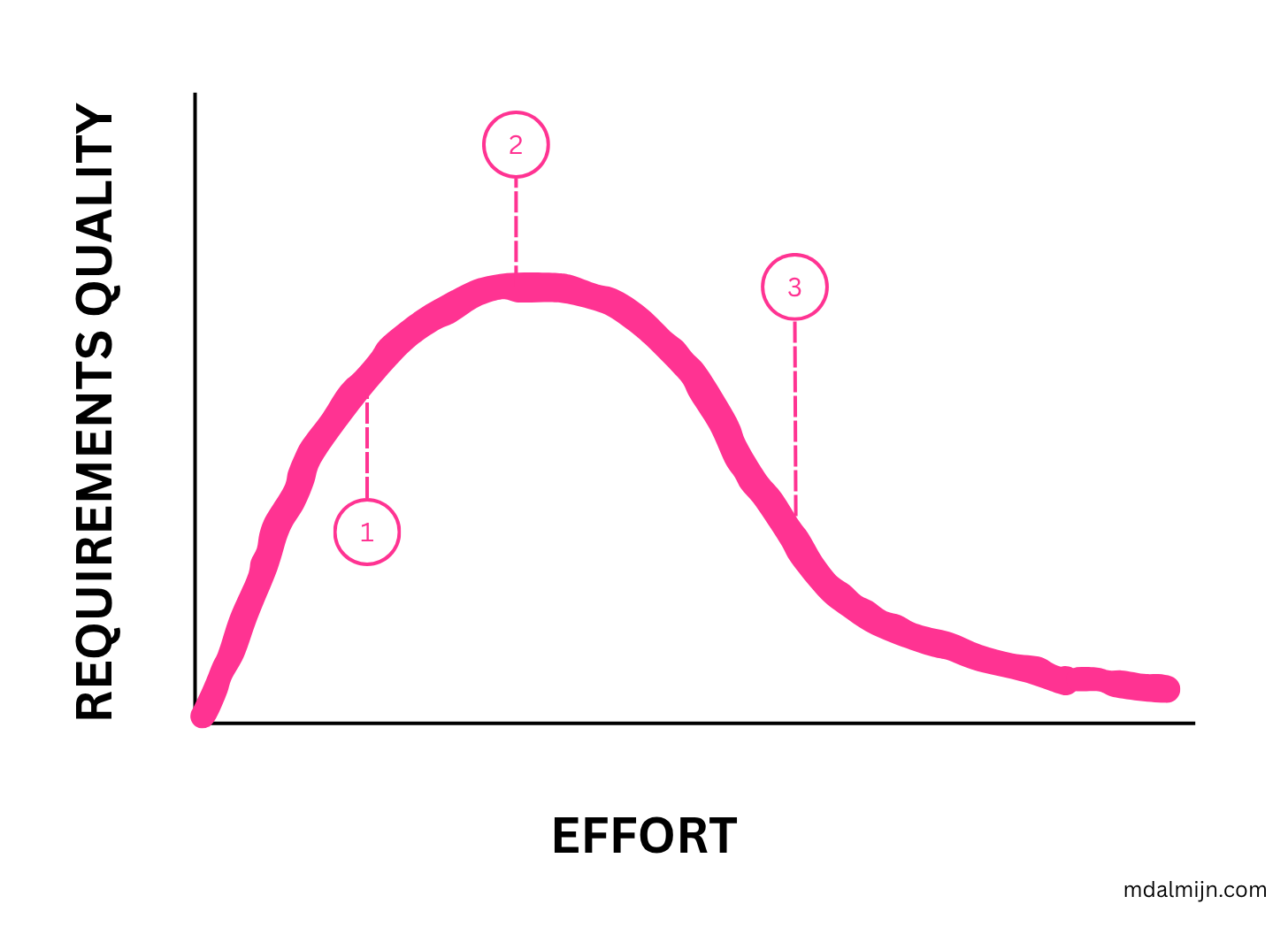

Should we create requirements at point 1, 2 or 3: under the hill, at the peak of the hill, or over the hill?

We can only answer this question accurately if we consider what’s the bottleneck for creating requirements.

What’s the Bottleneck For Requirements?

You might be thinking that what matters most for requirements is that we describe everything as exhaustively and accurately as possible. You would be mistaken.

The biggest bottleneck for requirements is our fallible and finite minds. Two things are crucial for discussing requirements with your team:

Comprehension

Recall

If requirements aren’t properly understood, you can’t discuss them. If requirements cannot be kept in our minds, then they will be extremely hard to take into account as a mental model while building something. Requirements must be kept in our minds as we do the work as much as possible for the best results.

If you write something down perfectly and exhaustively, unless you consider how our mind works, it will hurt comprehension and recall. Here’s the curve once again.

Imagine we start at the middle of the hill. Now our fallible mind comes into play, which has a tendency to make our requirements worse:

Cognitive overload. If what we’ve written causes cognitive overload, there are too many things covered at the same time, then it’s difficult to discuss requirements together. Ideally, we discuss requirements where they are still simple and unrefined, because that’s the best way of preventing this cognitive overload.

Loss aversion. The moment we make something required, by talking about it as a requirement, it’s difficult to remove. It usually sticks around, even if it’s unnecessary or doesn’t add value.

Addicted to addition. Research shows that if you give people a puzzle where the solution can be solved in two ways: by adding or removing a piece, then 80% will choose to add a new piece to solve it.

To make matters worse, we also have to consider the nature of complex work. The following two fogs frequently muddy the waters before starting the work:

Fog of Beforehand. Before we start working on something, is actually the worst point in time to formulate all requirements. By doing the work, we discover all the requirements.

Fog of Speculation. In statistics we call this over-fitting. Faced with uncertainty and a lack of information and/or understanding, we make wrong assumptions. We inject our requirements with (wrong) conjecture and speculation. We end up making our requirements worse.

Now, let’s get back to our original question: how much time should we spend on formulating requirements before presenting them to the team? Should be we under (1), on (2) or over the hill (3)?

If we’re at point 3, over the hill, the what happens most of the time is that we end up making our requirements worse. The team suffers from cognitive overload, because the requirements have been too fleshed out. We suffer from the the Fog of Speculation which we don’t remove, because suck at removing. Our tendency to add, ensures we inject even more speculation as we discuss the work.

Because we suck at going back when we’re over the hill, we spend more effort to make our requirements even worse. Better is actually worse.

If we’re at point 2, there will be a natural tendency to push the requirements over the hill to lower quality. Cognitive overload, loss aversion and the fog of speculation can all kick in to ensure we cross the point where our requirements begin becoming worse.

What does this mean for you as a Product Manager?

In short: worse is better. You should begin discussing requirements near the bottom of the hill with your team.

Lazy Requirements: Worse is Better

When formulating requirements, there is an (unknowable) optimum amount of time you should spend on them. Spend less effort and the quality goes down, spend more effort and the quality goes down too.

Why does this happen?

If you don’t think enough about your requirements, they will be shoddy and under-prepared. If you think too much, they will become muddled with conjecture and speculation, with the end result being the same: shoddy requirements.

The problem is that shoddy requirements through not spending enough time on them can be easily spotted. Shoddy requirements through spending too much time on then are much more difficult to notice, as they give the impression of being thorough and accurate.

In reality the shimmer of shoddy gold-plated requirements is far worse and more blinding than shoddy ugly requirements. As we believe we were diligent and exacting, while in reality we’ve completely disconnected our work from reality and due to the gold shimmer we usually only notice it when it’s too late.

In short, as a Product Manager, it’s really important to have lazy requirements. It doesn’t matter we don’t know the optimum amount of time to spend on our requirements. Present your requirements when you’re at the foot of the hill, and collaborate to push them slowly up the hill together.

Worse is better.

Nobody on the team will have cognitive overload and there won’t be any projection of false certainty going on. We’re in this together. We will write it in our language and in a way that everyone can understand. Maybe we can even decide to reframe the problem before any concrete acceptance criteria have been formulated yet.

Nothing causes cognitive overload quicker than a perfectly described ticket with rock-solid acceptance criteria that the team hasn’t seen before. When formulating requirements, no matter what you do: don’t go over the hill. That’s were terrible things happen, that we will usually only discover when it’s too late. Remember, premature optimization is the root of all evil.

Slowly climbing the hill together will always work better than quickly throwing the requirements over the hill to your team. Requirements that are over the hill, get thrown even further in the abyss after first contact with your team.

If you understand this concept, it also becomes painfully clear why using AI to write requirements is a recipe for disaster.

There is no substitute for doing the work, as by doing the work, what we write down becomes much less important than what we all intuitively understand without even looking at what we’ve written.

Provocative and useful, Maarten!

Two asks:

1. First, what concrete signals tell you a PM is already over the hill before a ticket hits refinement?

2. Second, which workshop moves help teams co-write just enough: story mapping, example mapping, or thin-slice prototypes?

I am also curious how you keep compliance and accessibility needs from bloating the scope. A checklist or before during after cadence would be gold.

Agree - and the big requirements up-front mentality lives on in big procurements.

It’s been striking after over a decade in cross functional software teams to recently see how bad things are for organizations pre-contract.

Endless rewrites in the fog of beforehand of procurement plans. Deep divisions between legal and teams involved. No actual learning from potential suppliers or customers. As if this somehow derisks the whole thing. Ugh!

I’m curious if you have seen collaborative procurement more focused on value and teamwork that is quick, gets results and a more humane experience for everyone involved?

I have worked a long time in software and feel the deepest impact of modern product approaches really needs to be applied earlier up the pipeline. Not just after contracts are signed: but to create them quickly and with wins for all.